Alfred the Great (i.e., Ælfrēd se Grēata) reigned in Wessex from 871 to 899. He was born in 849 at Wantage, Oxfordshire to Æþelwulf and Osburh. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he was sent to Rome at the age of four to be anointed king by Pope Leo the IV.

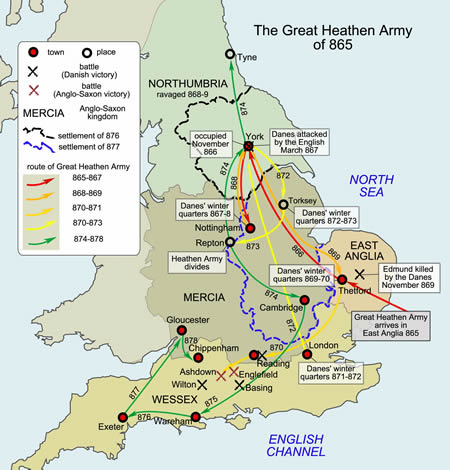

In 865, England was attacked by the Great Heathen Army, a Viking horde intent upon conquering the four kingdoms. With his brothers Æþelbald and Æþelberht both crowned and killed, the third son Æþelræd became king. Alfred is not mentioned during the reigns of his eldest brothers until the succession of the third son, Æþelræd, when he was given the title Secundarius by the Bishop Asser.

Starting with the skirmish at Englefield on December 31, 870, Alfred and his brother saw nine battles within a year. Æþelræd died on April 23rd, following the Battle of Merton, placing Secundarius Alfred on the throne of Wessex. While organizing his brother’s funeral, the English suffered a loss at an unknown location and again at Wilton in May 871. Alfred was forced to make peace with the Danes. The Vikings withdrew from Reading that to Mercian London in the Winter of 871, probably laden with significant Danegeld. The peace lasted until 876, though the Vikings remained active in other parts of England.

In 876, the Danes attacked and occupied Wareham in Dorsetshire. Alfred was again forced to negotiate with the Vikings. The two sides exchanged hostages, made oaths, and swore upon a holy ring of Thor. The Danes broke their oaths however, killing hostages and escaping in the night to Exeter in Devon. Alfred blockaded the Vikings there, forcing them to retreat back to Mercia. In January 878 the Vikings attacked again, this time taking Chippendam where Alfred was spending the Christmas holiday. Alfred escaped with a small band into the marshes of Somerset. At Æthelinga íeg (i.e., “Isle of Princes” aka Athelney), Alfred and his men likely reinforced an ancient fort and were able to rally local militias from Hampshire, Somerset, and Wiltshire. At this time, all of England had fallen to the Vikings except for Alfred’s meager resistance in the marshes of Wessex.

After four months at Athelney, Alfred gathered all the remaining forces of Hampshire, Somerset, and Wiltshire at Ecgbryhtesstan (i.e., Egbert’s Stone). From there, his army clashed with Guthrum’s Vikings at the Battle of Edington in May 878. Alfred was not only victorious but he pursued the Danes to Chippenham. After stranding the Danes in Chippenham for two weeks, the Danes sued for peace. The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum established two kingdoms and the conversion of Guthrum and 29 of his chiefs to Christianity. Guthrum took the name Æþelstan. The land ceded to Guthrum would become the Danelaw.

Following the treaty, there was a relative quiet across the kingdom. Alfred had to contend with a number of small raids and skirmishes, but nothing on the scale of Ivar and Guthrum’s incursions. On one occasion the Danes constructed a fortress outside the Saxon city of Rochester, but were chased back to their boats by the army of Wessex. In 886, Alfred reclaimed London and placed it in the care of Æþelred, his son-in-law and an ealdorman of Mercia.

In 892 and 893, Danes from the continent invaded England again. This time bringing 330 ships with wives and children, bent on colonization. On division of the Danes moved northwest and were defeated by Alfred’s son Edward at Farnham, Surrey. For the next couple years, the Anglo-Saxons chased the Danes across the country. Finally, Alfred managed to obstruct the River Lea and contain the Danish ships north of London. In 896/7, the Vikings abandoned their campaign and retreated to East Anglia, Northumbria, and the continent.

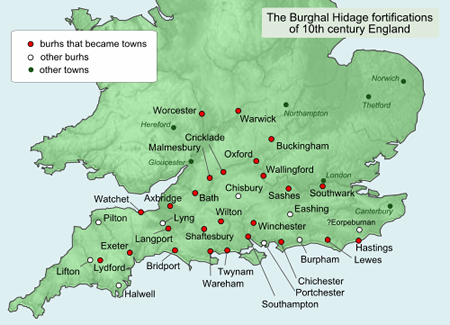

During the years that followed, Alfred implemented sweeping changes to both his military and country. Instead of sending his soldiers forward in long shield walls, he established a network of 33 burhs (i.e., fortified towns) at strategic locations throughout the kingdom. The burhs were each separated by 19 miles so that the army could respond to any attack within a day. Each burh was responsible for supporting a number of men according to the Burghal Hidage. In total, one in four Wessex freemen were needed for the 27,000 man army.

In 896, Alfred ordered the construction of a small fleet of longships. The ships were twice the size of Viking warships, numbering 60 oars each. Though better protected they were less maneuverable than their Viking counterparts. This resulted in an almost comedic battle where the heavy ships were stranded at low tide, forcing the sailors to exit the grounded ships and fight on land. The outnumbered Danes fled to their ships when the tide returned, and rowed away past the heavier, stranded English ships. The Danes suffered too many loses however and two ships were driven against the Sussex coast. The shipwrecked Vikings were brought before Alfred at Winchester and hanged.

In addition to military reforms, Alfred issued a 120 chapter domboc (i.e., Doom Book), based on the Decalogue, the laws of Ine of Wessex, and other predecessors. The domboc itself was confusing, contradictory, and poorly organized. Despite this, he seemed devoted to the ideal of judicial fairness, spending a great amount of time reviewing judgments made by his ealdormen and reeves.

Perhaps one of Alfred’s greatest legacies was his commitment to education. He required all officials to be literate and sought to educate his children, those of his nobles, and “a good many of lesser birth” through court schools. He had a number of Latin works translated into Old English, and sponsored the compilation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. Alfred is credited with translating and supplementing a number of works himself “sometimes word for word, sometimes sense for sense”. In the preface to his translation of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Alfred wrote:

“Consider what punishments befell us in this world when we neither loved wisdom at all ourselves, nor transmitted it to other men” and “Then when I remembered all this, then I also remembered how I saw, before it had all been ravaged and burnt, how the churches throughout all England stood filled with treasures and books, and there were also a great many of God’s servants. And they had very little benefit from those books, for they could not understand anything in them, because they were not written in their own language. As if they had said: ‘Our ancestors, who formerly held these places, loved wisdom, and through it they obtained wealth and left it to us. Here we can still see their footprints, but we cannot track after them.’ And therefore we have now lost both the wealth and the wisdom, because we would not bend down to their tracks with our minds.”

Alfred the Great’s crown (previously the Crown of St. Edward the Confessor) was melted-down by Oliver Cromwell during the Interregnum. An inventory of the crown jewels made by Parliament in that same year, described it as:

“King Alfred’s Crowne of gould wyerworke, sett with slight stones, and 2 little bells, 79 1/2 ounces at £3 per ounce, £248 10s.”

Parliamentarian Sir Henry Spelman described it better:

“It was of very ancient work, with flowers adorned with stones of somewhat plain setting” in a cabinet inscribed with the words “Haec est principalior corona — qua coronabantur reges Aelfredus, Edwardus”

King Alfred is believed to be buried at Hyde Abbey Gardens. His remains were moved to the site by the Norman King Henry I. In the 16th century, King Henry VIII had Hyde Abbey destroyed, but ledger stones at the gardens (placed in 2007) supposedly mark his final resting place. Some suspect that King Alfred’s remains might have been moved to St. Bartholomew’s chapel, also in Winchester. An ongoing investigation is studying that possibility.

- “King Alfred and the Anglo Saxons: Walk in the footsteps of a great ruler“, RadioTimes, 2013-08-23

- Map of “Great Heathen Army” created by “Hel-hama”, Wikipedia

- Coin images from “Ancient Art“, Flickr

- Photo of “Athelney Monument” by WurzelDave, WunderPhotos

- Map of “Burghal Hidage” created by “Hel-hama”, Wikipedia

- “Alfred the Great“, Wikipedia

- “Pastoral Care“, Bucknell University

Pingback: ISO Ælfrēd the Great | Rediscovering Angelðeod